For Jean

“Twink” is gay slang for a young man with a slim, boyish build, often characterized by little to no facial or body hair. Many self-identified twinks embrace feminine traits and an androgynous appearance. However, as time passes, facial hair grows, hairlines recede, and wrinkles start to appear, leading to the loss of the twink’s youthful appearance —“Twink Death”.

While it might sound a little dramatic or funny, the rapid rise in popularity of this concept highlights some bigger issues about beauty standards and ageism in queer culture.

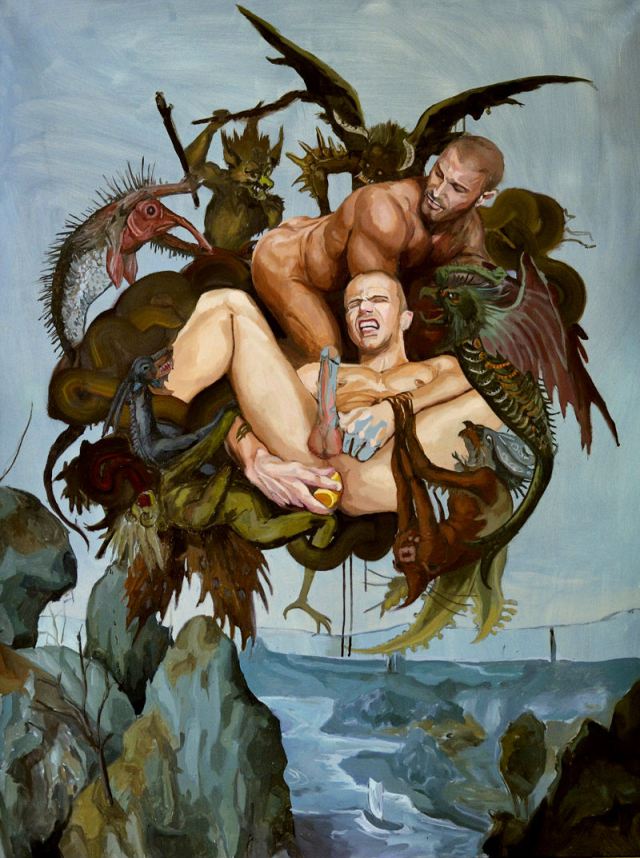

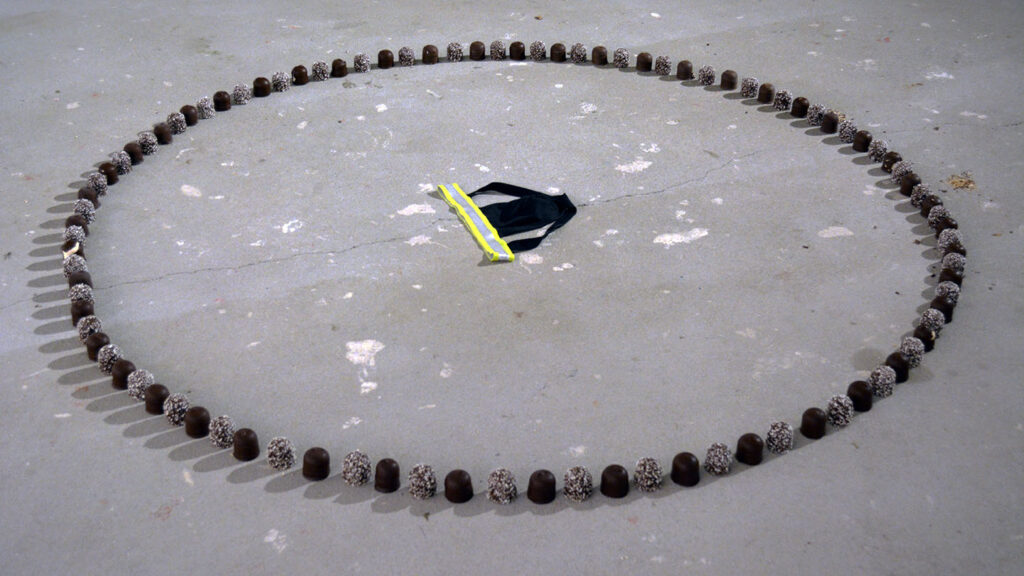

A Camp Symbol of Memento Mori

The installation consists of a jockstrap surrounded by a carefully arranged circle of Schwedenbomben. Their delicate shells, which protect the soft interior, crack under the slightest touch. This echoes the vanitas tradition, particularly the Baroque motif of desserts in still lifes, symbolizing the impermanence of life and the futility of earthly pursuits. However, the schwedenbomben add a layer of irony: as mass-produced, inexpensive treats, they contrast sharply with the classical depictions of memento mori. Their kitsch appeal aligns perfectly with camp aesthetics—a style deeply rooted in gay and LGBT culture that embraces exaggeration, theatricality, and artifice to subvert traditional norms. In this context, schwedenbomben can be seen as a potent symbol that fuses these two vastly different aesthetics and meanings, offering a camp reinterpretation of memento mori.

Oil on panel. 43.7 x 68.2 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

The desert in Baroque still life functions as a meditation on the impermanence of life and the futility of earthly pursuits.

Pleasure over Practicality

At the same time, both the jockstrap and the Schwedenbomben function primarily as sources of pure pleasure. Sweets, packed with sugar, offer no real nutritional value. Instead, their taste, look, and smell are designed to heighten the experience of indulgence. Similarly, the jockstrap barely covers the skin, functioning less as a practical garment and more as a means to enhance the body’s sexual allure. Together, through a significant overlap of symbolic meanings, they emphasize the fleeting nature of sensual pleasure.

A Queer Ritual

But where is the body? Is it a summoning, an offering, or both?

Is it a food offering?

The lying on the ground jockstrap evokes the absence of the body. It may symbolize the person it once belonged to, or perhaps something they desired. This ties seamlessly with the Schwedenbomben, hinting at food offerings for the dead—a tradition that spans cultures and continents. In Mexico’s Día de Muertos, vibrant altars brimming with food honor and connect with departed loved ones. Similarly, the Slavic ritual of Dziady involves leaving offerings for ancestral spirits. In China’s Hungry Ghost Festival, food is presented to wandering souls to ensure they are nourished in the afterlife. In West African yam festivals, ceremonial offerings to ancestors serve to honor their memory and seek blessings. These practices underscore the universal human need to bridge the gap between the living and the dead.

or is it a Summuning?

Meanwhile, the circle suggests a protective barrier—separating the summoner from the unknown forces they seek to invoke. In Western esoteric tradition, materials like salt, flour, or chalk were used to form magic circles. Yet here, the Schwedenbomben are used, introducing a humorous twist—a sprinkle of absurdity.

Echoing the ancient stone circles, the piece draws on the traditions of Land Art and Arte Povera from a queer perspective—because even in the afterlife, camp deserves a seat at the table.

These ritualistic aspects of the installation also resonate with deeper themes of collective mourning and personal loss within the queer community. So, who is this queer ritual for?

HIV/AIDS Epidemics and Mental Health Crisis

In 1991 Felix González-Torres placed a pile of wrapped candies in a gallery to commemorate the loss of his close friend to AIDS — Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.). Visitors were free to take candies away. The gradually diminishing pile of candies mirrored the deterioration and disappearance of patience consumed by the disease. The artist transformed private loss into a public act inviting the audience to engage in a shared experience of mourning and reflection.

Photo by Spangineer.

Photo by mark6mauno.

Similarly, my piece reflects the grief I carry from losing my dear friend, Jean Cueto, who took his own life. His death is a reminder of the struggles faced by many of us within the LGBT community. According to a 2023 Trevor Project survey, 18% of LGBT youth have attempted suicide—twice the rate of their peers in the general teenage population. This devastating statistic highlights the enduring effects of minority stress, which amplifies feelings of invisibility and hopelessness and too often leads to the loss of young lives.

Humor as Resistance

Yet, despite the heaviness, there is room for a gentle smile—a bittersweet nod to life’s absurdities. The Schwedenbomben and jockstrap are a playful juxtaposition, combining sensual desires and intimacy with the inevitability of decline. Humor, after all, is often the queer community’s most powerful form of resistance: a way to embrace our fragility while laughing in the face of despair. This piece stands as both a personal tribute to Jean and a call for solidarity, visibility, and care within our community.